My Legs Were Praying

Permanent link

Last month I found myself on the side of a highway outside Montgomery, Alabama, with a group of 300 strangers. We represented three countries, 29 states, and hundreds of personal stories and purposes that brought us together.

The event was the 50th Anniversary Walking Classroom, an immersive educational experience commemorating the 1965 March for Voting Rights. We replicated the 54-mile journey from Selma to Montgomery that 300 activists and faith leaders marched to shed a light on racial injustice and break down the significant barriers to the ballot box that African-Americans faced almost a century after they were legally allowed to vote.

Photo credit: Albert Cesare

“Like the children of Israel leaving Egypt, we marched toward the Red Sea, and we were on our way, not knowing what was before us,” wrote Amelia Boynton Robinson, one of the organizers of the 1965 marches.

Raised in an interfaith home, social justice is one of the things that ultimately attracted me to Judaism. Reading about how many young Jews flocked to the March on Washington and risked violence on Freedom Rides and at Sit-Ins filled me with pride and a sense of obligation to ensure civil rights for everyone.

I’ve always thought that activists have this moment where they make a choice between what is easy and what is right – and I’ve wondered when my choice would present itself. It turns out you sometimes need to take the first steps of a journey before you realize that you’ve already made your choice.

Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, who marched next to Martin Luther King, Jr. as the crowd swelled to 25,000 upon reaching Montgomery in 1965, connected faith and activism when he wrote that, “for many of us the march from Selma to Montgomery was about protest and prayer. Legs are not lips and walking is not kneeling. And yet our legs uttered songs. Even without words, our march was worship. I felt my legs were praying.”

That line has always spoken to me, but miles into the walk I began to feel it on a deeper level. Deeper than my blisters and sunburn, louder than the spirituals we sang in the pouring rain, I felt in my bones throughout those five days of marching that I was doing something meaningful and holy.

It was good I had my legs to pray, because I was left speechless more often than I could have ever anticipated.

When a foot soldier who marched in 1965 embraced and thanked me for honoring her march 50 years ago, I was speechless.

When I crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge, without danger or hesitation, I was speechless.

When Amelia Boynton Robinson drove alongside us one afternoon on the highway outside of Selma, I was speechless.

When I stood at the memorial to Viola Liuzzo, the only white woman to die while protesting during the Civil Rights Movement, I was speechless.

When our 300-person march swelled to thousands on the last morning, as we filled block after block of downtown Montgomery and assembled in front of the capitol, I was speechless.

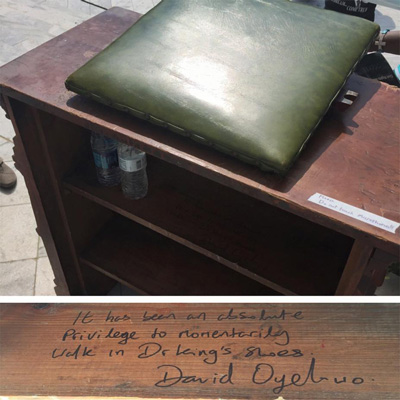

After the formal program ended, I walked up the steps of the capitol, and found the podium King stood at while giving his “How Long? Not Long” speech 50 years before, down to the day. I laid my hands on it, took hold of this piece of history that had supported a man who lived and died for freedom and equality, and prayed for the strength to bend the arc of the moral universe toward justice.

I work with young people for a living, and I see it as my responsibility to create a world for them that allows them to learn and grow, and where it is safe to be themselves. When I read about Trayvon Martin and Michael Brown, I think about the 17- and 18-year-olds that I love, and about the endless potential they have to influence the world and effect change, something stripped from young black men with alarming frequency.

Last week I was leading a Rosh Hodesh group for high schoolers at one of my synagogues. The maintenance staff had turned on the alarm, forgetting we were in the basement, and we set it off while looking for Nutella on a snack break. The alarm blared through the building and alerted the local police. I calmly explained to the responding officer that I was there to run my group, and that I was very sorry that this is the third synagogue I may or may not have set an alarm off at in my four years working with congregations. He took my name, thanked me for my time, and left.

I couldn’t help but ask myself, would that interaction have gone differently if I had been someone other than a 5 ft. 4 in. blond woman? If I were a different race or gender, if I appeared physically intimidating, how would the officer have approached me? If I had been leading a group of five 15-17 year old young black men, instead of white Jewish girls, would he expect one of us to be armed? To have broken into the building, instead of being on a mad hunt for some Nutella? The teens I work with can usually be approached by a police officer and feel safe. They receive the assumption of good will, rather than a weapon drawn on them.

On my first night in Selma, I sat down at dinner across from Harrison, a black 13-year-old. Because I spend all of my time with teenagers, and am socially awkward around my peers – like a 13-year-old – Harrison and I became fast friends, and I spent a lot of miles talking to him. We quizzed each other on Harry Potter trivia. We shared in the woes of being an only child and how we felt it probably wasn’t too late for our families to adopt brothers for us. We raced Fitbits to 10,000 steps each day, and we shared photos of our dogs on Instagram. It was no different than getting to know my teens at home in Chicago.

A week later, Harrison’s mom posted this to Facebook: “Today's homeschool lessons include where to put your hands if the car you are in is ever pulled over and how to ‘yes sir’ even when you know you're not wrong.”

It has never occurred to me to teach my teens deference to authority. In fact, I sometimes worry I’m going to get angry phone calls from parents for helping to raise radicals that I put out into the world with the express intent to make social change. I take joy in teaching them to be agitational when it comes to community organizing – to shake the system until it notices them and can’t help but hear their voices. And I’ve never thought that it could put them in fatal danger.

That is entrenched racism. That is privilege. That is why I walked and thought and prayed my way from Selma to Montgomery; it’s not enough for only my teens to be safe. Emma Lazarus wrote, “until we are all free, we are none of us free.” Repairing the world requires activism on behalf of everyone. Social action is just that – action. It comes from a life of movement, continuing to put one foot in front of the other, praying with our legs, marching toward justice.

To read more posts in the "Repairing Our World" blog series, click here.

.jpg)