Debunking the JAP myth

Permanent link

The shirt in question

Only once have I been asked if I killed Jesus.

The girl, a ninth-grade peer of mine at the time, with chutzpah enough to ask me this question, hailed from a small, Jew-free Minnesotan town. When I mentioned in passing to her that I was Jewish, the next words out of her mouth were, “Didn’t the Jews kill Christ?”

That’s the only time I’ve encountered blatant anti-Semitism—black-and-white-no-question-this-is-clearly-anti-Semitism anti-Semitism. But what scares me in our culture today is the not-so-blatant anti-Semitism. It’s a much subtler and more insidious form of Jew bashing, so pervasive in American society—particularly in Jewish circles, of all places—it’s considered both acceptable and even comical.

I don’t lack a sense of humor but the stereotype of the Jewish American Princess—the JAP—is offensive to me as both a Jew and as a woman. I once saw this image, defined in urbandictionary.com as a “bitchy, spoiled, gold-digging Jewish female,” emblazoned on an Urban Outfitters T-shirt with the caption “Everyone loves a Jewish girl,” surrounded by dollar signs and purses.

And worse yet, it’s our children, our community who are the market for this image—we’re expected to accept it, buy it and thus perpetuate it.

The JAP image dates back to the 1950s, when Jews themselves, many still feeling like outsiders relatively new to this country, coined the stereotype as a defense mechanism, according to Riv-Ellen Prell, a University of Minnesota anthropologist and professor of American studies, who has lectured on Jewish gender types. The image then became popularized during the 1970s when consumerism took hold of the country, according to Prell, who contends that the JAP, like the other ubiquitous Jewish female stereotype—the Jewish mother—is depicted as uncontrollable, with endless wants.

Today, even though we are no longer outsiders, the JAP stereotype has stuck. A few years ago, the Urban Outfitters’ tee, which became so controversial it was later pulled from the shelves, was part of a larger line of ethnic T-shirts. One, for example, says, “Everyone loves a Catholic girl,” with miniature crucifixes decorating the slogan, while another declares, “Everyone loves an Italian girl,” illustrated with pizza drawings. A silly concept for a clothing line? Perhaps. Harmful to society? No.

But then there’s the Jewish tee, “Everyone loves a Jewish girl,” surrounded by dollar signs and purses! Why, rather than money symbols, couldn’t the T-shirt designers have slapped some Magen Davids onto the shirt? Even bagels would have been better. Either of these would have been more comparable to the imagery on the other shirts.

These days, there are a huge variety of threads that help Members of the Tribe and friends of MOTs literally wear their religious identity on their sleeves, like those offered on Jewcy and Kosher Ham.

To me, any of these images and slogans are far more innocuous than the message that the shirt in question delivers. After being flooded with complaints, Urban Outfitters Inc. redesigned the T-shirt sans dollar signs and purses, an action that the store says it took out of sensitivity to the Jewish community. I applaud the company for taking the offensive shirt off the market, but we as a Jewish community ought to be concerned about what this shirt represents. Shouldn’t we worry that the image of the Jewish people is one synonymous with money and materialism?

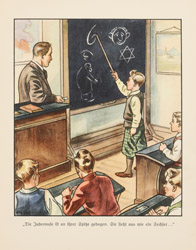

Think about the dangerous origins of the rich/greedy Jew image. The stereotype was born many centuries ago when Jews were relegated to occupations dealing with money. Ever since, throughout history, Jews have been targets of this hateful stereotype—an image that came to a head in Nazi Germany when Hitler employed it as a tool in the initial stages of his hate campaign against the Jewish people. The Holocaust is our most tragic reminder of what happens when a stereotype becomes accepted as a general truth, an accurate way to portray an entire people.

Yet now, we seem to have forgotten this lesson. In today’s society, Jews are no longer just victims of negative Jewish stereotypes—we’re perpetrators of them. Aren’t we the ones projecting and buying into these stereotypes? After all, aren’t our Jewish daughters the ones who were buying these ridiculous T-shirts? Is this message of materialism what we want to convey to the outside world and—more importantly—to our own Jewish children?

Many Jews figure that it’s okay for “members of the tribe” to tell JAP jokes because a Jew can’t be anti-Jewish. I disagree. To me, these jokes aren’t funny; they are mockery, betraying a lack of self-respect, becomes self-destructive. Furthermore, if we ourselves perpetuate these negative Jewish images, then how can we criticize non-Jews for doing the same?

I can recall three instances on first dates when two minutes into our time together, my Jewish date has asked me, “Does Daddy pay for your apartment?” Mind you, these men hardly know me, let alone have they ever seen where I live, yet they assume that because I’m a Jewish girl in the big city, I’m rich and spoiled. (Note to my Jewish sisters: If this ever happens to you, feel free to cut the date short and walk straight out the door.)

To me, JAP humor is particularly repulsive because the stereotype is untrue. That’s not to stay there are no Jewish women out there who fit the princess stereotype, but there are also non-Jewish princesses, Jewish princes and non-Jewish princes too.

My wonderful circle of Jewish girlfriends in no way fits the JAP stereotype. They are kind, independent, bright, and ethical young women—each a mensch. These are the qualities—the qualities of a mensch—that I enjoy sharing with my friends, qualities that I hope the world will recognize.

This is my hope for my 3-year-old and 9-month-old Jewish nephews—and for my future children as well—to grow up in a world without prejudgments and stereotypes. That’s something for us to strive for.

.jpg)