Small but growing numbers discover new cultural horizons and deeper commitment to ideals of faith

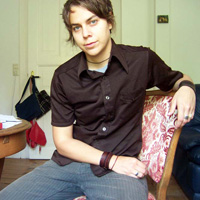

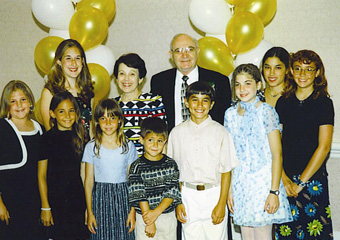

U.S. Army Armor Company Commander Johnie Bath with his family, his wife, Jamie Adelman, and their twins, Netanya and Nathaniel.

Saying the Shema in Baghdad

Prayer helped U.S. Army Armor Company Commander Johnie Bath through tough times in the Iraqi war zone.

Though limited food options made it hard for him to keep kosher and he wasn’t able to practice the Hebrew that he had been learning back home, he often chanted prayers, particularly the Shema, a Jewish prayer pledging allegiance to God. “My rabbi told me to say the Shema twice a day,” he recalls. “I said it easily twice a day, probably more. Whenever things got a little hairy, it was reassuring to say the Shema and I felt that I was covered just in case.”

Today, Bath feels like his prayers have paid off. His wife, Jamie Adelman, and their 1-year-old twins welcomed Bath home this spring after he completed his one-year deployment in Iraq. A career Army man, Bath, who is currently based with his family in Fort Riley, Kan., joined the military 16 years ago, after graduating from high school. “I was a young, patriotic kid, wanting to find excitement,” he says. “I jumped at the opportunity to go overseas and jump out of airplanes.”

He and Adelman, who married two years ago, settled in Lincolnwood while Bath served in the Illinois National Guard. When he requested active duty status, his first assignment took him to Baghdad, where he helped prepare the Iraqi army for combat.

Before his deployment, however, Bath had accomplished two life-changing events. First, he stood by his wife’s side for the birth of their two children, daughter, Netanya, and son, Nathaniel, who underwent heart surgery as an infant, but is now healthy.

Then, shortly after their birth, in February of 2007, Bath converted to Judaism at Congregation B’nai Tikvah, a Conservative synagogue in Deerfield. Growing up in a small Ohio town, Bath had felt little to no religious attachment to his Christian origins. Longing for a religious identity, he had explored Judaism even before meeting his wife, but dating her solidified his desire to become a Jew by choice.

Today, especially in his dangerous line of work, he finds comfort in his Jewish identity.

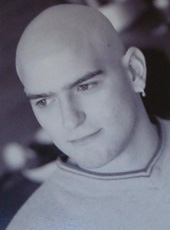

Rabbi Maj. Ira S. Ehrenpreis (below) having fun with the guys in his unit after a 100 yd low crawl through a mud ditch. Ehrenpreis would frequently send Jewish care packages to the men in his unit.

Proud to serve

Like Bath, other Chicago-area Jewish troops and chaplains are part of the small Jewish minority of the U.S. Armed Forces who have been serving this country for the past seven years in the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq.

The Chicago Jewish community mourned the loss of one local soldier last winter. Cpl. Albert Bitton, a 20-year-old Jewish medic serving his seventh month in Iraq. Bitton was killed in February—along with two other soldiers—in Baghdad when an IED (improvised explosive device) struck their Humvee. He had joined the Army in 2005 after graduating from Ida Crown Jewish Academy in Chicago, with aspirations of receiving the training and financial help to become a surgeon some day. In a letter to his friends, Bitton assured them that he would remain devoted to Judaism while serving his country, pledging to pray each day: “I will always remain a Jew, every step of the way.”

There’s debate over how many Jews serve overseas. While the U.S. Military says that 0.3 percent of personnel are Jewish, the Jewish Community Center Association’s (JCCA) Jewish Welfare Board (JWB) Jewish Chaplains Council maintains that the number is higher—1 percent, which translates to some 8,000 troops, additionally, 29 Jewish chaplains currently are dispersed around the world.

“It’s hard to get an exact count,” says Rabbi Harold L. Robinson, a retired U.S. Navy rear admiral and director of the JWB Jewish Chaplains Council. “The military no longer keeps those kinds of statistics in any reliable way. Jews tend to not necessarily declare their religious identity on official forms, especially if they’re going to the Middle East.”

The U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) makes provisions for personnel, including Jews, to observe their faith without interfering with military operations. In the Army, soldiers are permitted to wear yarmulkes (skullcaps) as long as they do not conflict with the wearing of protective headgear, according to Lt. Col. Anne Edgecomb, of the Department of the Army Public Affairs. Beards often worn by religious Jews, however, are unauthorized because they may interfere with gear, said Edgecomb.

In past wars, Jewish troops hid their Jewish identity more often than they do today because anti-Semitism is less of an obstacle in the military than in decades past, according to Rabbi Maj. Ira S. Ehrenpreis, a Jewish chaplain returning from Iraq this summer. Even during the first Gulf War, Jewish soldiers were encouraged to hide their religious identity and write “Protestant B” on their dog tags, an internal code indicating to military chaplains that they were Jewish, according to the Jewish Telegraphic Agency. Yet today, the military does nothing to hide the religious identity of any personnel, according to the DOD, and Jews usually reveal their Jewish identity on their dog tags.

Larger military overseas posts offer Shabbat and High Holiday services as well as kosher and vegetarian meal rations. In addition, the Jewish Soldier Foundation and New Jersey-based LaBriute (to your health) Meals have teamed up to provide thousands of kosher meals to Jewish troops overseas.

Recruits celebrate shake their groggers (noisemakers) at a Shabbat service on the holiday of Purim.

Making deals with the Almighty

Last Passover, Ehrenpreis hosted a seder for U.S. army troops in an unlikely place—one of Saddam Hussein’s former palaces in Baghdad.

As the soldiers concluded the seder with a Passover favorite tune, “Echad Mi Yodea,” (Who knows one?), they heard a mortar attack outside the walls of the palace. They turned their faces downward and didn’t move until it was all clear. “We finished with this wonderful feeling, [knowing the significance] of holding the seder in Saddam’s palace,” says Ehrenpreis, one of only three Jewish chaplains currently stationed in Iraq.

Ehrenpreis is a long way from his former life as a special education and Talmud teacher in Far Rockaway, N.Y. An observant Jewish rabbi who later relocated to West Rogers Park with his wife and five children, he joined the chaplaincy in homage to both his religion and his ancestors.

“I thought it was an opportunity for a Kiddush Hashem, (an action that brings honor, respect, and glory to God),” he says. “I wanted to travel the world and introduce myself to thousands of people who have never even spoken to a Jewish person, let alone a rabbi,” he explained. “It’s important to have a Jewish presence in the military because this is the country that my grandparents were able to come to after World War I, escaping the Cossacks, and seeking refuge. My rebbe (rabbi) said that every day we should raise the American flag because we have the privilege of freedom and religion.”

So 13 years ago, Ehrenpreis shaved his beard and the next day entered a New Jersey training center for chaplains with 245 Southern Baptists and other Protestants, five priests, and one Jew—himself. He is the first and only rabbi in the Illinois National Guard, in which he served for three years, and has spent a decade on active duty, twice in Kuwait and once in Iraq.

In the Persian Gulf, the rabbi wears two hats. He and the few other Jewish chaplains in Iraq coordinate religious coverage such as Shabbat services, Jewish holidays, and kosher food. In his second hat, he acts as a battalion chaplain for 500 soldiers, most of them from Louisiana, and none of them Jewish. His soldiers are 40 percent Catholic, 45 percent Protestant, and 15 percent unaffiliated. He acts as a confidant and a spiritual guide for his troops, leading them in prayer at trying times.

“Let’s say they’re going on a dangerous convoy,” he said. “If someone feels particularly anxious and would like a particular prayer, I may give him a hug and then we say that prayer together.”

Ehrenpreis himself was accustomed to praying often in Chicago, but he stepped it up a notch when he arrived in Baghdad. “When I am home in West Rogers Park, I daven (pray) morning, afternoon, and evening,” he says. “Yet, I realized that I was probably doing more davening over here in Baghdad, talking more to the Almighty, making deals: ‘If I come back alive, I promise I will learn one full page of Gemara (Torah commentary).’”

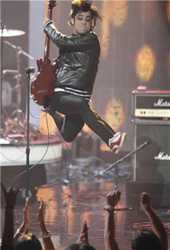

Army Captain Jason Blonstein praying at the Jewish Chapel at West Point.

‘Sacred time’: Fridays from 7-9 p.m.

Basic training at the Great Lakes Naval Recruit Training Command (RTC) is a world that’s regimented and time-controlled. No iPods, no cell phones, no hairstyle choices. Yet, one aspect of life not dictated for soldiers is the freedom to pray and express their religious identity.

Shabbat services—strictly from 7-9 p.m.—is when the Jewish Community Centers of Chicago (JCC) reaches out to Jewish recruits at RTC, the third-largest Navy base in the country, located in Great Lakes, north of Chicago. The volunteer chaplaincy program, a model program for the country started by JCC leaders last year, coordinates rabbis and cantors to lead Shabbat services and sometimes holiday services at the training center.

“Coming to Shabbat services is probably the only opportunity the recruits have in a given week to call each other by their first names, to talk with one another, to share their feelings,” says Rabbi Nina Mizrahi, director of JCC’s Pritzker Center for Jewish Education and coordinator of the chaplaincy program, who also sometimes leads services. “They come at 7 p.m., but at 9’oclock, they’re out of there. They don’t have watches. It’s an incredibly sacred time for them.”

Last year, Rabbi Harold L. Robinson—a retired U.S. Navy rear admiral, and director of the JCC Association’s Jewish Welfare Board (JWB) Jewish Chaplains Council—and representatives of the Navy Chaplain Corps alerted JCC to the need to fill more chaplaincy positions at the RTC. The U.S. Navy has only eight chaplains, but requires 12. And the need for Jewish chaplains is even greater. There hasn’t been a full-time rabbi stationed at Great Lakes since its last military rabbi left the base two years ago. To fill the void, JCC, along with the Chicago Board of Rabbis, worked with the RTC to scout rabbis and some cantors to lead services at the base.

Each week, some 15-35 recruits, primarily Jewish and from a wide range of socioeconomic and Jewish backgrounds, attend Friday night services. “As a Jew [in the Navy], sometimes it’s easy to feel like you’re the only one,” says Lt. Cdr. Joshua Taylor, a former RTC recruit. “The chaplaincy program allows us the opportunity to connect with other Jews and to get a sense of community that might otherwise be lacking.”

While rabbinical styles vary, each Shabbat service includes elements of a prayer service, learning, and an oneg (Shabbat party), and some offer music or other forms of entertainment. On Shabbat, Mizrahi asks those recruits who comfortable enough to introduce themselves and discuss a given topic such as their families back home or a moment in the past week when they appreciated nature.

“You have to create a sense of community in the context of the service,” says Mizrahi. “So they’ll straggle in and sit, and some know each other, but by the end of that time together, we need to have gotten to a place that’s communal—and we do—and that’s what’s extraordinary.”

A West Point bar mitzvah

Jason Blonstein celebrated his bar mitzvah, but not at the age of 13. Rather, his special day arrived years later and far from home—as a 21-year-old recruit at West Point, the New York military academy, where approximately 1.5 percent of the 4,000 students are Jewish. Though he was raised as a Jew in his hometown of Palatine, Blonstein—now an Army captain—engaged in few Jewish rituals growing up. Yet, once he arrived at West Point, Judaism piqued his interest.

“We would go to synagogue a lot of times on Friday nights because our freshman year we couldn’t leave [campus],” he says. “It was a way to socialize and get some food.” He even joined, and later led, the Jewish choir, in part to “to meet girls.”

Yet, there was more involved than grub and girls. “I just don’t think I had a positive Jewish influence when I was younger, but I had those influences around me at West Point,” he says. “I took advantage of the opportunity to learn more about my religion and culture.”

Then, during his junior year at the Academy, Blonstein chose to have a bar mitzvah. He would wake up early in the morning to study Torah with the rabbi on campus. Blonstein’s mother and father—a former Marine—and other family and friends flew to West Point for his ceremony.

After graduating from West Point, he trained on tanks and was commissioned as second lieutenant and then as an armor officer in Fort Knox, Ky. From 2001-2006, he served in Bavaria, Kosovo, and later was deployed to Balad, Iraq, for one year.

Though Blonstein found comfort in his Jewish identity while stationed in Iraq, religion wasn’t the first thing on his mind when lives were on the line. “It becomes more about the guy next to you,” he ssys. “My role as an officer was to try to accomplish the mission and bring back all my soldiers.”

Two years ago, Blonstein left Iraq and moved home to Chicago, where he currently works for an energy company, and plans to volunteer in the Jewish community. He encourages more young Jews to join the military as an alternative to mainstream college education. For Blonstein, serving was a way to say thank you. “Going into the military,” he says, “was a way I could give back to a country that I felt had already given me so much.”

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)