The fictional girl

Permanent link

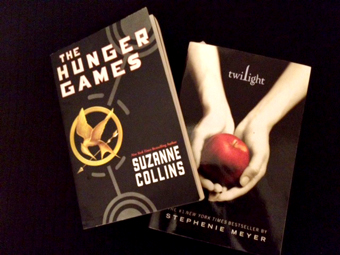

Oy, I am knee-deep in teen literature. I just read Twilight and The Hunger Games, back-to-back.

I tried to shield myself from the Twilight-obsessed for as long as I could muster. I blame my co-worker, with whom I frequently discuss favorite television shows at work. I admitted to her that one of my must-see shows is The Vampire Diaries, and she forced the Twilight book into my hands. I'm shamefully old to be watching a CW show about teen vampires, werewolves and witches, but I can't help myself. There is a part of me that will always be 13 years old. The Vampire Diaries merges my nostalgia for those Dawson's Creek days when I was a young teen, with my adult fascination with vampires. It just so happens, Kevin Williamson created both shows.

I've only read the first book in each of the Twilight and Hunger Games' series so far, and my fascination already runs deep. I can't stop talking about them. I respect The Vampire Diaries and Dawson's Creek for their use of strong female characters, despite a somewhat clichéd and slow-as-molasses love triangle plot. The female protagonists in these shows are intelligent, self-aware and wise beyond their years. (It's also worth noting that The Vampire Diaries, like Twilight, began as a book series, though I have not read the series.) While reading Twilight, however, there was a part of me that wished leading lady, Bella, would just meet her demise already.

I'm not the first person to ever connect the dots between vampire stories and puritanical ideals. Still, the pairing was glaringly obvious in Twilight. The 13-year-old in all of us can relate to Bella's teenage vulnerability, obsessive boy crush and utter clumsiness in front of Edward. These are the aspects of the book that drew me in, along with the mystery around the beautiful and super-human "family" in small town Washington. However, I'm not 13, and many of the book's readers likely are. In my opinion, as an early introduction to romance and relationships, this book fundamentally fails, and teens won't necessarily have the tools to question why. In my perfect world, high schools would incorporate women's studies courses in their curriculums and teach this book as a cautionary tale.

In many ways, I think Bella and Edward's relationship mirrors that of an abusive relationship. Bella always watches what she says around him, fears angering him and suppresses all wants and needs of her own to keep him in check. Bella is the gatekeeper of Edward's uncontrollable urges. It's Bella's fault when Edward loses his temper; it's her fault when he cannot control his sexual urges; it's her fault when he cannot control his "hunger." The book is one step away from a Lifetime movie about rape victim blaming. The book unfolds as a sort of Adam and Eve story, in which Bella becomes enamored with Edward, her allure is too strong, and he can't help himself but to be around her. She is thus to blame for putting herself and her family in danger—a reason for which she must be protected. Edward vows to protect her at any cost, but she must abide by his rules, and dare not tempt him.

The book becomes a creepy and tentative game of chicken between the two of them, in which Bella is convinced she has met her love, her reason for living—her future matters not. And because she has urges, feelings and desires, she must risk her life. Bella is at Edward's mercy because she knowingly entered into danger (desire). She'll live, if she listens to him and doesn't get ahead of herself. Twilight is like a disturbing how-to manual for the abstinence movement.

As a latecomer to both Twilight and The Hunger Games, reading them one after another offered an unexpected opportunity for comparison. Hunger Games protagonist, Katniss, is the anti-Bella (not to be confused with antebellum). If I were teaching one of these mythical high school women's studies courses, I might follow my Twilight lesson with one on The Hunger Games. In a stripped-down, post-apocalyptic world, in which there is no time to idly fantasize, Katniss' actions are a product of instinct, obligation, integrity and intelligence. In some ways, she is the prototype to which all teenage girls should aspire—and thank goodness, some do. I wish I had this book as a teenager. Many books I read in school and for pleasure had detached male protagonists, to whom I could scarcely relate. Katniss is a far cry from Holden Caulfield.

The book is purposefully vague, as Katniss navigates survival and love. I believe author Suzanne Collins didn't want to make The Hunger Games a cheesy romance novel (though I don't know yet about books two and three). She makes the book about Katniss and her ability to stand on her own against all odds. The story dances around coming of age themes, in which Katniss begins to question her feelings about her fellow tribute, Peeta, but her curiosity never consumes her—if it did, she would die. In fact, Katniss "plays" the game by pretending to be in love, and models being in love by drawing from clichés and memories of her parents, never having experienced the adult feelings herself. Katniss is not offering a loveless world, but one in which intellectual autonomy plays a leading role. By comparison, Katniss must feign love to survive; Bella must forfeit her free will for love.

Both of these books represent a sort of clash or crossroads girls and women face today. Many still buy into the fairy tale, in which the woman must be rescued. Others are ready to see women take on the world using their brains…and perhaps, a bow and arrow. At 13, I wanted a cleverly scripted fairy tale; my adult self knows better.

.jpg)