Late to the Animorphs Party

Permanent link

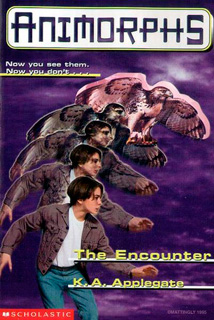

I missed the Animorphs series the first time around. Man, in the ‘90s, you saw those book covers everywhere you went: one kid transitioning into a fly or a bear or a dolphin or some other creature. And there were always two tons of them, right? They were just a little young for me when they started coming out (or I might have been too invested in showing off that I was reading Watership Down instead), but, uh…

I’m reading them now.

I’m kind of hooked.

There are some stories that, no matter how dodgy the premise, I will always inhale. Animal transformation is one of them. When I was six, my fondest wish was to be a were-rat, thanks to a healthy diet of Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles and Mrs. Frisby & The Rats of NIMH. My hometown used to have the best video store imaginable (RIP, Magic Video), and in addition to helping me discover obscure foreign costume dramas, I also became obsessed with the The Shaggy Dog and The Shaggy D.A., old Disney movies about a boy (and later a district attorney) who’s cursed by an ancient Egyptian ring to become a sheepdog at inconvenient times. A good werewolf story? I’m always in.

Animorphs should have been right up my alley, but nobody ever told me what they were actually about, and I was quite content at the time with the Redwall books, another talking animal series of my heart.

.jpg)

But let me talk for a minute about Animorphs, if I’m not repeating something you already know. The basic premise carries more than a whiff of Invasion of the Body Snatchers. Five friends find a UFO crash with a dying alien inside, who gives them the power to morph into any animal they touch, in order to fight an imperialist race of parasitic aliens called Yeerks. So, kids saving the world plus paranoia about grownups plus awesome superpowers—why wouldn’t kids eat this up?

We know, however, that if that were it, no one would really care. But our heroes have problems, one of which is that you can’t stay in your morph for more than two hours. Otherwise you get stuck, and there’s no going back. (Three guesses as to whether this becomes a plot point!) Beyond the prospect of Earth being colonized by a vicious race of slug creatures, the Animorphs have human problems too. One kid lost his mother two years ago. Another deals with bullies. Another can’t figure out why her best friend won’t talk to her anymore.

The author (or many authors; it should come as no surprise that a franchise this successful and prolific has ghostwriters) does some neat characterization things too. The “girliest” character, the one who loves shopping and looking pretty, is also the battle-ready bruiser of the group; her favorite morph is an elephant. This girl could have been pigeonholed so easily as dainty, or scared, or vain. So many of my friends describe these books as “formative;” I’d much prefer that a kid’s formative experience tells her that she can be any combination of likes and qualities that she wants than that she be pigeonholed into lazy, poisonous “types” that we shouldn’t question.

Not only that, but the whole horror of the Yeerks stems from the way they replace and repress identity. If you’ve got a Yeerk slug in your brain, you’re still trapped alongside it, a bystander to what this evil being does with your body, your voice and your face. Pick your metaphor: kids (and the adults they become) understand what Yeerks are, and they remember the hardship—and the heroism—of standing up to them.

I also really like what these books do about depicting animals. It’s not Disney: animals aren’t just humans with four legs. This summer, at one of the farmer’s markets at Daley Plaza, a representative from the forest preserve brought in a rescued hawk to help educate passersby about Illinois wildlife.

“What’s his name?” I asked, then hesitated. “Her name?”

“We don’t name our animals, because wild animals aren’t people and they aren’t pets,” the ranger said. “We want kids especially to understand that animals exist independently of us and inhabit an entirely different world apart from us.”

Animorphs tackles that well, I think. Yeah, the kids are still themselves when they change, but they also have to cope with different instincts in different bodies. Other animals don’t talk to them or give them advice or form relationships with them. It’s a remarkably unsentimental and powerful statement, really. These animals are themselves, not something you try to impose on them.

I’m not that far into the series, though I’ve been warned that “the last 15 or 20 books decline significantly.” (I love that we have to disclose on a scale of dozens of books. That’s awesome.) But you see why I’m hooked—and the danger’s even greater with my midterm work piling up. Because, let’s face it: in addition to all the stuff I’ve just said, these books are fun. The stakes are high, the group dynamics are great, the kids are real—it’s just fun reading, and you don’t really need more justification than that.

That said, these big questions aren’t new, and it’s not weird to address them through a conceit like transformation. Ovid did it pretty well, and we’re still reading his Metamorphoses two thousand years later. So, reflecting on another Halloween gone by, a day that’s dedicated to letting your freak flag fly, here’s a reminder to read what you like, get what you want from it, and be who you’re supposed to be.

.jpg)