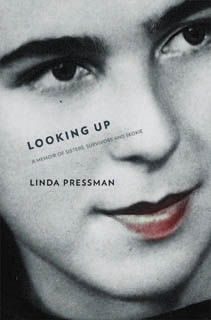

'Looking Up'

Permanent linkA daughter of survivors tells the 'second chapter' in their story

.jpg)

Life—in many ways—was a Jewish Norman Rockwell painting for Linda Pressman, growing up in Skokie in the 1960s and 70s.

Her childhood included all the usual trappings of suburbia of that era—manicured lawns, her beloved banana seat-decked bicycle, and frequent trips to meet the Good Humor truck jingling down the streets of her neighborhood.

Her idyllic upbringing glided along in stark contrast to that of her parents, Holocaust survivors from Eastern Europe. While Pressman grew up in post-war Skokie, one of the safest locales in the world to be Jewish, her parents spent their formative years in the most unsafe place in the world to be Jews.

After immigrating to Chicago following the war, her parents raised a full house of seven daughters, Pressman the second to last. She chronicles her experiences—funny, wacky, and heartbreaking—in her new book Looking Up: A Memoir of Sisters, Survivors and Skokie (CreateSpace), a story offering a unique perspective on the Holocaust, one generation removed from the war. In conjunction with Yom Hashoah (Holocaust Remembrance Day), Pressman, who now lives in Scottsdale, Arizona, will return to Chicago to speak about her book in April.

Helene Burt, Pressman's mother, hailed from Lithuania and Poland, and then survived the Holocaust in the forests of Eastern Europe. Pressman's father, Harry Burt (who passed away in 1975), and his family fled their hometown in Poland, and spent the war in the frozen tundra of Siberia. After the war, Pressman's parents met each other at a displacement camp in West Germany, before eventually making their way to the States.

Unlike many Holocaust survivors, in the immediate years following the war, Helene Burt "was loud with the Holocaust, in your face with the Holocaust," as Pressman writes in your book. While her father was more taciturn, Helene talked about the war to her daughters every chance she got. As comfortable as her mother was telling her story, Pressman was just as uncomfortable hearing it, finding it too hard to wrap her mind around a world so removed from her, so overwhelmed by her mom's oversimplified anecdotes that always ended with "…and then the Germans killed them all." It was only in her adulthood that Pressman came to terms with listening to her mother's stories and even sharing them through her writing.

In advance of her visit to Chicago, I spoke with Pressman by phone.

How do you characterize children of survivors?

Linda Pressman: There are different types of children of survivors. There are the types that really attach to their parents' stories and who can talk about it…And then, there are the types like my sisters and I who built a wall and didn't want to hear it. My mom—now age 81—would start talking and we would run out of the house. I heard a filtered amount—I heard the bomb, I heard the grenade—and that was enough.

As time went by, you decided you wanted to tell your parents' story. What changed for you?

As I would share the story [of growing up in Skokie at writers' workshops], the other students would say they want to know more about …I can't talk about what it's like to have Holocaust survivor parents and not say that this story happened. The reason why they…hoarded food and wouldn't spend money on anything that wasn't food or shelter was because of [what they went through in Europe]…To be able to tell what kind of a crazy, miraculous, heartbreaking, and yet funny childhood I had, to tell what that their experiences led to has been an honor to tell.

Describe the dichotomy between your mother's upbringing and yours as a girl in Skokie.

My mom would talk about the war, and I'd look outside and there was no forest and there were no Nazis…Her experiences led her to believe that it wasn't safe to be Jewish. She was very young—11 years old—when the Nazis marched into her town. And then, until she got to the U.S. at 19, it was very much not a good thing to be Jewish. In her stories, every single person ends up dead, every story has a bad ending…But here I am living in the 1960s in Skokie and it seemed like the stories were really obscure. Now I know that the war hadn't happened that long before, [but back then] it seemed like she was talking about a different planet. She was talking about a place where it wasn't safe to be Jewish. In Skokie, everyone—I mean everyone—was Jewish. There couldn't be a safer place to be Jewish than Skokie in the 1960s.

How has being the daughter of survivors affected your worldview?

Finding out that your parents have suffered is a really disconcerting moment in the life of any child. As a [little] kid, my impression was my parents were like other parents. I couldn't hear the accents because they were too close to me to actually hear them. As I left home and went to school, it occurred to me that my parents were different than other parents...I started realizing that my parents came from this different place and suffered and they weren't just safe here being Bobby soxers and dancing to the Big Bands in the 1940s. It has made me feel protective of her all these years.

How does your mother feel about your book?

My mom could never stop talking about the Holocaust. It was a problematic issue for me. I would call her up and we would be talking about dinner or shopping or doing something typical and suddenly she'd change the subject and we'd be talking about the Holocaust…and then when I gave her my book, it was like this huge burden was lifted from her. She feels relief that her story will live on without her having to talk about it all the time.

As the next generation, do you feel a responsibility to tell their story?

I don't feel that I'm the best person to testify about the Holocaust. I do feel like I'm the best person to testify as to what happens after the war. Here are these two people who come out of Siberia and out of the forest. The question children of survivors can answer very eloquently is 'Did they live happily ever after?' I can't ever tell a Holocaust story as well as a survivor actually could and thank goodness there are so many testimonies about that. But I can tell what kind of parents they were and how sad or happy they were or how they lived the rest of their life. To me, that is a very compelling second chapter to the story.

.jpg)